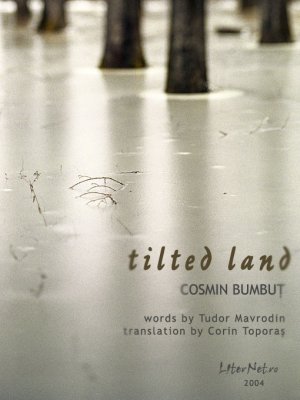

Bumbuţ's lands

Alina Andrei

The long road from the city to the forest, from people to nothingness, the camera hanging on your neck like a burden, is nothing but a welcomed evasion. Road, evasion. What a cliché! Could be, but why shouldn't we call a spade a spade? Just for the sake of originality? No. No need. Of course I am assuming, of course I know nothing about the circumstances in which those photographs were taken, I don't personally know the author, I have no idea if he's easy-going or sullen, if he prefers the birch trees to the poplars. All I know is that he has a hell of a knack for taking pictures of people (excuse my French) and that, as another photographer said three years ago, 'you've got to have balls to shoot like him', which doesn't stop me from saying whatever crosses my mind without being self-righteous. I am no critic (what an irritating species: they believe they have the right to say 'A wanted to show this' or 'B felt that', as if they were able to get through to the heart and brains of the photographer / painter / writer and rip them out like in a bad horror movie). Right.Now I can tell you what I see in these photographs... Let me begin with what I don't see. I see no people. Which is good because when I am fed up with the hot concrete, the pushing crowds, the honking cars, the ringing phones, the cursing people and the tasteless music, I rest my eyes on a tilted skeletal tree lost near a bus stop. More trees means more rest for the eyes, as it is known that there are no people in the woods unless you're unlucky, and even then there's few of them (hikers, foresters, woodcutters, dropouts). And they're not all together, they're scattered among the trees. Say there's one man for each thousand trees. That's good.

But that's bad, too (excuse my indecision). These landscapes have the major inconvenience that they are short of Bumbuţ's portraits, those faces that become fascinating all of a sudden once imprinted on film. Therefore I am willing to forgive those shortcomings as those pictures look good... on paper.

Why is it good?... because his landscapes give a respite even to my ears. No loud noises coming of them, just silence. Silence. The air is cold, but not freezing, enough to prick your nose and ears and to make you take another drag on your cigarette. The car is waiting on the side of the road the radiator purring. It's warm inside. You're outside, your boots in the dirt, looking at the emaciated trees and the punctiform birds in the distance. There's a wooden fence out there that I simply love, it's like I made it myself, should I have been able to weave those thin sunburnt branches tight enough to keep them from falling apart. At night, the deer step on that ice, through the shoots springing from the water. Thumb-sized fish swim under the thin ice and frogs sleep through the winter. I wouldn't mind if they croaked, as 'ribbit' is not a noise, it's still a blessed silence, no high-pitched voices, no hysteric screams. A dull happy smile on my face I'd watch the golden road strip stretching over the snow powdered land, a tree trunk crooked just to make the shadow look good. It's just like it used to be straight like a soldier in full regalia and I bent it just a bit to make its slightly tilted shadow flow towards me. That blue snow is too clean, I feel like sticking my fingers in it or writing foolish words with a long stick just too startle any local that would cross them. I don't know what. An absurd no-rhyme poem, a verse from a Christmas carol, 'Our Father, which art in heaven'. Or not. I could try to vindicate the silence, through words, of course, yet words scribbled on those snowy hills rather than articulated ones. The fact that people got rich on tapes of exotic birds, dolphins, waterfalls or storms infuriates me. Can you record on tape the sound of a tree loosing its foliage on a soil impregnated with rotten grass, acorns and hoof marks? It would be a blasphemy. It's stupid to listen to something like that at your desk, in front of your computer, when everybody asks of you to be effective. When you stand like that in the snow you don't have anybody breathing down your neck hurrying you to do something.

You'd rather hurry catch a train or a car, get to the desert with mounds of frozen, yet not dead, earth, and imbibe with silence until you forget that behind those trees there is a village and beyond that village there is a city. The camera's click is a blessed silence as well. You don't have to answer it with a yes, no, maybe, yeah or whatever. Stay there until you can't take the silence anymore, until you've had enough of absurd fences that don't separate anything, and come back when you feel like it. Take that winding road and never look back.

Should you have a friend, take him there, in those photographs. Let him enjoy the silence, the prickling fresh air, like sparkling water up your nose. Should he be afraid of the desert deprived of human beings, tempt him with a little wooden house hidden in the woods where he can find steaming cheese pies (cheese from the cows that ate the grass in the photos), fresh coffee on the stove and a wise old lady who knows better stories than Vasile Voiculescu. And an old man sitting on a bench with a bottle of home made plum brandy hidden from his old ball and chain.

Should you have an enemy, the kind who talks too much and keeps breathing down your neck, take him there, too, in the middle of nowhere. In the summertime so he won't freeze to death. Tie him to a tree (by the foot so he can move around a little like a dog on a leash). Leave food, water and a blanket next to him and leave him there for a while. For his own good it's sound to let him talk to himself, then to make grandiose speeches to the tree he is tied to, to other trunks, branches and leaves, let him cry to the birds circling above hid head and to squirrels, let him spew out his venom on hedgehogs and groundhogs. For a few hours he'll be fuming, then he'll enjoy imagining in detail the pain he'd inflict on you when he'll break free, he'll scream like crazy just to hear his voice. After a few nights he'll learn to take pleasure in the silence, to enjoy the leaves, the cows ruminating, the cuckoos and the quails. He'll talk less when you'll set him loose. However, before taking such radical measures you might want to consider sharing these photographs with him. Or you might tell him to mind his own business and remind him the story about the dust. 'For dust you art, and unto dust shalt you return'. Maybe he'll get it.

(translated by Corin Toporaş)